Israel’s Founding Principle Selectively Applied

The differing immigration experiences of Ukrainians and Ethiopians Jews, leaving war-torn countries to resettle in Israel

By Noa Avishag Schnall | July 6, 2023

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, The Jewish Agency for Israel initiated Operation Immigrants Come Home to bring Ukrainian Jews to Israel, and a month later launched “Aliyah Express,” a program to expedite the immigration process.

Israel encourages Jews to come live in Israel and grants them citizenship under the country’s Law of Return. Yet the promise of safe haven seems to be applied selectively to fit an ideal demographic.

The Judaism of Ethiopians wasn’t recognized as valid until the 1970s, and the immigration process for Ethiopians during the recent Civil war, and prior, was markedly slower and more scrutinized than the process for Ukrainian and former Soviet Union immigrants fleeing the invasion.

Many Ethiopians wonder, while their country was at war — and now, when it comes to reuniting families of recognized descendants of Jews — why they were not, and are not, treated with the same urgency as their Ukrainian counterparts?

7 Stories

“There’s no such thing as Jewish refugees,” said Pnina Tamano-Shata in an interview in July 2022, the former Minister of Aliyah and Integration and the first Ethiopian-born Minister to serve in the Israeli Parliament. What she means is that under Israel’s Law of Return, currently, almost anyone with at least one Jewish grandparent is eligible for Israeli citizenship.

In the days immediately following the invasion, the Israeli government called on Ukrainian Jewish refugees to immigrate to Israel. The nation removed bureaucratic hurdles to secure the refugees’ arrival as quickly as possible.

The Jewish Agency, a semi-governmental agency tasked with helping Jews who are interested in immigrating to the country, set up transit stations in Poland, Romania, Moldova and Hungary, launching Aliyah Express.

Rabbi Dov Lipman, a former member of the Israeli Parliament and founder of Yad L’Olim, an aid organization that works to assist Ukrainian Jews returning to Israel, described a system for processing applications that was “very lenient,” requiring some minimal amount of proof of Jewish identity. For example, an immigrant could give a verbal confirmation that she “prays at a certain Chabad,” and that would suffice, said Rabbi Lipman in an interview in July 2022. She could then provide the rest of her documents once in Israel.

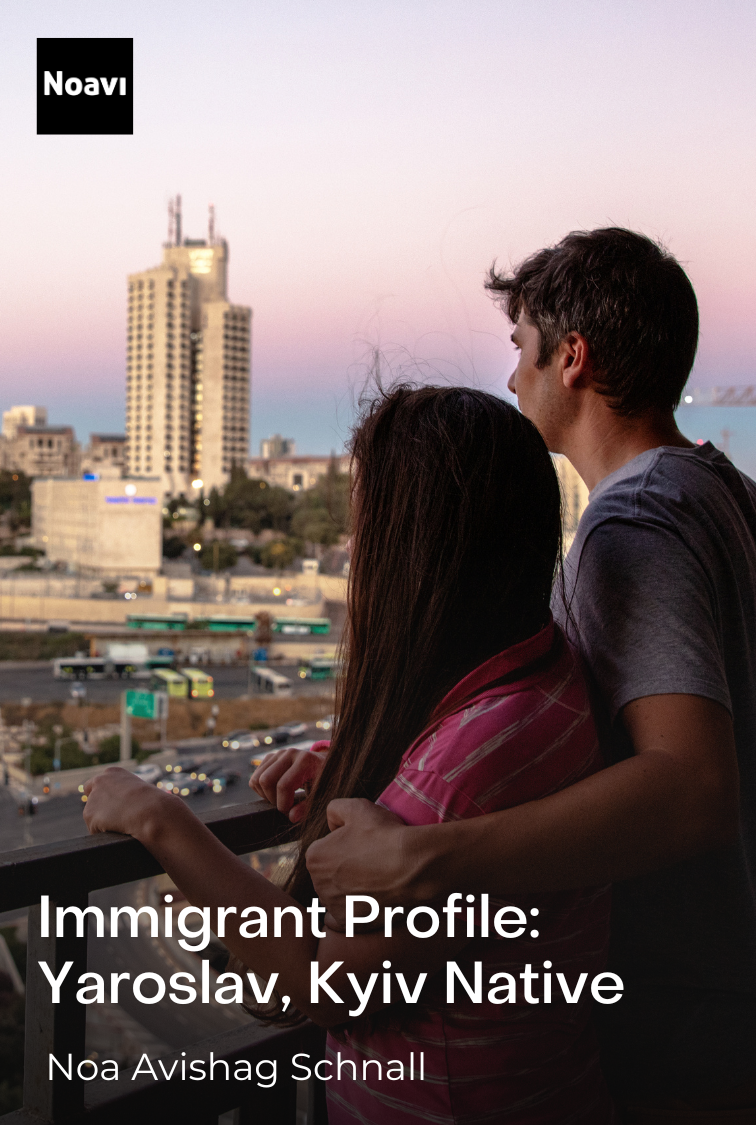

Yaroslav, 35, Anya, 30, and Maria, 3, in their room at the Jerusalem Gardens Hotel, provided by the Israeli government. The Kiev natives fled the city in the early hours on the morning of the Russian invasion, but Yarsolav was unable to exit due to martial law restrictions. Eventually, he escaped illegally. Learn more about the family in the ‘7 stories’ above.

The option to establish Law of Return eligibility on arrival in Israel was newly created as an emergency measure to expedite the process specifically for Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion, and was not available prior. As of February 2023, one year since the Russian invasion, 16,000 Ukrainian migrants have been flown to Israel, and 50,000 have been granted entry from Russia under Israel's Law of Return, per Jewish Agency numbers.

HOW WE GOT HERE

Israel was established in 1948 as a homeland for Jews, including those seeking refuge from persecution. Paradoxically, it created approximately 750,000 Palestinians refugees in the process, and a country of dispossesion. The Israeli government does not recognize their right to return to the territory. Though Ethiopian Jews have lived in Israel since its establishment, unlike other Jews, they were not eligible for citizenship under Israel’s Law of Return until 1975, after the Chief Rabbi of Israel finally recognized the community’s Judaism.

Over many decades, tens of thousands of Ethiopian Jews, and Ethiopians that Israel distinguishes as ‘of Jewish descent,’ have come to Israel with the help of the government and many external aid groups. But the Israeli government has aided in their immigration slowly and reluctantly, even recently when Ethiopia was in the midst of civil war. Officially, a peace deal was reached in November 2022. However, renewed ethnic violence and deteriorating regional stability threaten the shaky political landscape.

Rina Ayalin-Gorelik, a lawyer and the executive director for the Association for Ethiopian Jews pointed out that Ethiopian airlifts happened largely because of the work of Ethiopian activists. “It didn’t start because of the state [of Israel], it started despite the state,” she said.

OPERATION TZUR YISRAEL

In October 2020, Resolution 429, pushed through by Tamano-Shata, outlined what would become Operation Tzur Yisrael, granting 2,000 Ethiopians entrance to Israel by that December through ‘family reunification.’ This made way for Ethiopian Jews, already in Israel, to unite with their first-relation family members back in Ethiopia, who Israel did not recognize as Jewish. However, the residency status of those immigrants was contingent on attendance in, and successful completion of, Orthodox conversion courses once in Israel, a stipulation that started in previous operations.

A month later, tensions between the Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and the leaders of the country’s Tigray region exploded into violence. Fighting there killed hundreds of thousands of people, displaced millions and spiraled into a humanitarian crisis before the two sides agreed to a truce last November.

A year after the start of the Ethiopian civil war, the Israeli government announced that a continuation of the Operation would begin in 2022, set to bring in another 3,000 people.

From inside the Tadesse family residence at the Tzfat Absorption Center. New Ethiopian immigrants reside in absorption centers for an average of two years before integrating into the rest of Israeli society. Orthodox conversion courses are part of their immigration agreement because their Judaism is not recognized upon arrival.

NOT JEWISH ENOUGH

When the last large-scale operation to bring Ethiopians ‘of Jewish descent’ to Israel concluded in 2013, Israel took a quiet position on the status of Ethiopian immigration for the foreseeable future, that reflected an end to governmental mass airlifts. On a zoom call in August, the Jewish Agency’s former spokesman and current Head of International Relations, Yigal Palmor, made the Agency’s position clear, “As far as we know, there are no Jewish populations in Ethiopia.” He added, “there could be a family here or a family there. If they haven’t identified themselves, we wouldn’t know.”

But, according to Ethiopian Israelis with family members still in Ethiopia, many still languish behind, awaiting their turn to immigrate, and have been desperately pleading their cases. Israel has repeatedly promised to bring over the people they call ‘the remnants of Ethiopian Jewry’ but it has yet to come through on its pledge.

The remaining Jews in Ethiopia have to produce proof of Judaism at a standard more stringent than all other diaspora communities to be eligible for Law of Return immigration; what is much more likely for them is to immigrate to Israel under the ‘family reunification’ path, even though that can take decades.

That method applies to the descendants of Ethiopian Jews who, while they identify as Jewish or of Jewish lineage, do not qualify under the Law of Return. Israel does not recognize them as Jewish and once they arrive in the country.

While some were forcibly converted to Christianity and have since returned to Judaism — like Jewish communities in Germany, Iran, Spain and Portugal — it is the Ethiopian community that has been singled out for draconian verification measures and waiting periods when it comes to their desire to emigrate.

Of the Ethiopians immigrating in the past three years, the overwhelming majority have done so via ‘family reunification.’ However, in the instances of Ethiopians Jews arriving to Israel via the Law of Return, unlike Ukrainians, there has been no accommodation allowing for the establishing of eligibility upon arrival, even during the recent Ethiopian Civil War.

THE ‘MAMTINIM’

Ethiopian Jews, who have applied to enter Israel through family reunification, are encouraged to relocate to Gondar or Addis Ababa and wait — sometimes for decades — waiting for their names to be called. Israel has a name for these Ethiopians, ‘mamtinim’, or "those who wait."

Jewish Agency centers in the area provide a place for prayer and sometimes food, but they must find and pay for their own housing. To supplement whatever local work they can find, they sell their homes and belongings. Some receive remittances from relatives already living in Israel. When the money runs out, or they can’t find work, they return to their villages.

Jeremy Feit, the president of Struggle to Save Ethiopian Jewry, a group that provides humanitarian relief, says that the average Jewish family in Gondar, a city in northern Ethiopia, waits 17 years to immigrate to Israel. In summer 2022, his organization distributed food aid to Ethiopians in Gondar and Addis Ababa, who, according to him, “are living actively Jewish lives, attending synagogue and sending their children to Jewish schools.”

ON ARRIVAL

On arrival in Israel, Ethiopian immigrants entering under the family reunification law are bused to absorption centers, some in the far reaches of the country, like Beit Alfa and Tzfat. Like all Jewish immigrants to Israel, the Ethiopian immigrants receive temporary financial benefits. But, uniquely, the Ethiopians’ cost of housing in the center is deducted from their benefit package. Inside, they are assigned apartments and must also provide their own food.

By contrast, Ukrainians Jewish immigrants fleeing the Russian invasion have the option of staying in all-inclusive government-funded hotels for two weeks (though Israel was previously offering stays of one month), with no deduction to their immigrant benefit packages. Multiple aid organizations and volunteers help them settle into their new lives in Israel. They also offer help in finding long-term apartments, mostly in Israel's central cities like Haifa and Jerusalem.

ROOT CAUSES OF DIFFERING TREATMENT

Efrat Yerday, the chairwoman of the Association of Ethiopian Jews, believes the disparity between the two groups is rooted in race. “Israel, like the rest of the world, usually prefers white people over brown and black people,” she said. The reason for that, she added, is because Israel “uses diaspora communities to promote its demographic interest,” and that the claim “fits in opposite ways to [former] U.S.S.R. immigrants and Ethiopian immigrants,” supporting the inflow of the former, and stymying the latter. Asked about claims of racism, a spokesman for Israel’s newly elected Ministry of Aliyah and Integration said that they had no comment.

Ayalin-Gorelik, who came to Israel at age four with her family from Ethiopia, before the airlifts, and with the help of an American aid group, specifies, “The establishment, which does not recognize us as Jews, this is what started the whole story of systemic racism.”

CLANDESTINE FLIGHT FROM TIGRAY

Filmon Atalay is among the 60 Tigrayans that were brought to Israel via Sudan on a secret Mossad mission in July 2021, and who said in an interview in August 2022, "we stepped over bodies to save our lives on our way to Sudan.” He recalls not being provided with much at his absorption center, and that he had to start life over from zero.

Shortly after the group arrived, their Judaism was challenged at a governmental level, in the media and in public demonstrations, accusing them of exaggerating the level of danger they were fleeing. “Instead of receiving us with blessings, they received us with hatred,” said Atalay.

ISRAEL, NOW

On Dec. 29, 2022 Benjamin Netanyahu was sworn in as Israel’s prime minister, in a right-wing coalition in which his Likud Party is the most moderate member. Minister Tamano-Shata was then replaced by Ofir Sofer, a member of the Religious Zionist Party. The coalition is considering restricting the Law of Return’s eligibility criteria from “child and grandchild of a Jew” to just “child.” This would require the person requesting citizenship to prove Judaism in the first generation, through a parent, rather than allowing it to be proven more broadly, two generations back.

The proposed change to the law would still be less strict than Law of Return eligibility requirements for Ethiopians, who are required to have proof of a Jewish mother (rather than also allowing paternal proof in first generation), and whose eligibility checks are handled and verified directly by the Ministry of Interior — the highest level of scrutiny — rather than the Jewish Agency.

Cheqle Tadesse, 55, holds his official, yet expired, residency certificate of a subsection of Gondar. In Amarigna, his religion is listed as “Jewish”. Cheqle and his family were made to wait 10 years before they were allowed to join their family members in Israel. Orthodox conversion courses are part of his family’s immigration agreement because their Judaism is not recognized.

As of July 2023, Operation Tzur Yisrael is nearing its end. The resolution that allowed for the Operation’s creation stipulated a limited number of Ethiopian immigrant entrances, and the new government has not authorized any more. The final flight is scheduled for the week of July 10th.

Though the war continues in Ukraine, the Israeli government has recently stopped granting free hotel access to Ukrainian Jews escaping the war. However, they can still claim Israeli citizenship through the Law of Return.

The waves of mass hunger and persistent displacement still resonate from Ethiopia’s recent war; and sixteen months on from its start, mass displacement, death tolls and tragedy continue to rise in Ukraine. The Institute for Economics and Peace published their Global Peace Index in June 2023, which revealed that in 2022 alone, there were “more than 100,000 deaths in the war in Tigray in northern Ethiopia,” and in Ukraine there were “at least 82,000 conflict deaths.”

A week after the Ukrainian immigrant operation was approved in February 2022, in a Cabinet meeting that would make headlines across Israel, Tamano-Shata accused her government counterparts of pushing forward quick solutions for those fleeing Ukraine, but falling silent when it came to Ethiopians, where the war began a year before. She had been “working tirelessly for Ukrainians to immigrate under the Law of Return,” but when it came to how the Cabinet felt towards the Ethiopians she said, “this is white man’s hypocrisy.” During the same meeting, in response, the former Diaspora Affairs Minister Nachman Shai joked, “European wars impact me more than war in Africa.”

In July 2022, the Chekol family just arrived from Ethiopia, including parents Aynu and Bleynesh, with their two boys Yenbev and Samniwo and baby Moloken on Bleynesh’s back. The Chekols waited 11 years in Ethiopia before they were approved to immigrate to Israel, before being bused to an absorption center.

_____

Daria Carmon contributed reporting.

Translation/ Transcription Services | Amarigna: Kalkidan (Qal) Fessehaye, Tigrigna: Kisanet Haile Molla and Meron Teferi, Russian: Hanna Flagarova

Video Colorist: Chase Coughlin

Carousel Design: Asad Ali

Parallax Design: Manoj Kumar Kandwal

Share this article via: